Law war handbook 2004

LAW OF WAR HANDBOOK

(2004)

MAJ Keith E. Puls

Editor

Contributing Authors

Maj Derek Grimes, USAF

Lt Col Thomas Hamilton, USMC

MAJ Eric Jensen

LCDR William O'Brien, USN

MAJ Keith Puls

MAJ Randolph Swansiger

LTC Daria Wollschlaeger

All of the faculty who have sewed before us and contributed to the literature in the field of operational law.

Technical Support

CDR Brian J. Bill, USN Ms. Janice D. Prince, Secretary

JA 423

International and Operational Law Department

The Judge Advocate General's Legal Center and School

Charlottesville, Virginia 22903

PREFACE

The Law of War Handbook should be a start point for Judge Advocates looking for information on the Law of War. It is the second volume of a three volume set and is to be used in conjunction with the Operational Law Handbook (JA422) and the Documentary Supplement (JA424). The Operational Law Handbook covers the myriad of non-Law of War issues a deployed Judge Advocate may face and the Documentary Supplement reproduces many of the primary source documents referred to in either of the other two volumes. The Law of War Handbook is not a substitute for official references. Like operational law itself, the Handbook is a focused collection of diverse legal and practical information. The handbook is not intended to provide "the school solution" to a particular problem, but to help Judge Advocates recognize, analyze, and resolve the problems they will encounter when dealing with the Law of War.

The Handbook was designed and written for the Judge Advocates practicing the Law of War. This body of law is known by several names including the Law of War, the Law of Armed Conflict and International Humanitarian Law. While these terms may largely be used interchangeably, for historical and contextual reasons, the Law of War will be used in this publication. Unless otherwise stated, masculine pronouns apply to both men and women.

The proponent for this publication is the International and Operational Law Department, The Judge Advocate General's Legal Center and School (TJAGLCS). Send comments, suggestions, and work product from the field to TJAGLCS, International and Operational Law Department, Attention: MAJ Keith Puls, 600 Massie Road, Charlottesville, Virginia 22903-1781. To gain more detailed information or to discuss an issue with the author of a particular chapter or appendix call MAJ Puls at DSN 521-3310; Commercial (434) 971-33 10; or email keith.puls@hqda.army.mil.

The 2004 Law of War Handbook is on the Internet at www.jagcnet.army.mil. After accessing this site, Enter JAGCNet, then go to the International and Operational Law sub-directory. The 2004 edition is also linked to the CLAMO General database under the keyword Law of War Handbook -2004 edition. The digital copies are particularly valuable research tools because they contain many hypertext links to the various treaties, statutes, DoD Directives/Instructions/Manuals,CJCS Instructions, Joint Publications, Army Regulations, and Field Manuals that are referenced in the text. If you find a blue link, click on it and Lotus Notes will retrieve the cited document from the Internet for you. The hypertext linking is an ongoing project and will only get better with time. A word of caution: some Internet links require that your computer contain Adobe Acrobat software.

To order copies of the 2004 Law of War Handbook, please call CLAMO at (434) 971 3339 or email CLAMO@hqda.army.mil.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

History of the Law of War ................................................................................................. Chapter

Framework of the Law of War ........................................................................................... Chapter

Legal Basis for the Use of Force .................................................................................... Chapter

Geneva Convention I (Wounded and Sick in the Field) .................................................... Chapter

Geneva Convention I11 (Prisoners of War) ....................................................................... Chapter

Geneva Convention IV (Civilians) .................................................................................Chapter

Means and Methods of Warfare ......................................................................................... Chapter

War Crimes and Command Responsibility ....................................................................... Chapter

Applying the Law of War in Operations Other Than War ................................................Chapter

Human Rights .................................................................................................................. Chapter

EXPANDED TABLE OF CONTENTS

History of the Law of War ........................................................................................................ 1

Framework of the Law of War ................................................................................................ 19

Legal Basis for the Use of Force ............................................................................................. 35

Geneva Convention I: Wounded and Sick in the Field .......................................................... 51

Geneva Convention 111: Prisoners of War .............................................................................. 75

Appendix A. CENTCOM Reg 27-13 (Determination of EPW Status) ......................... 116

Geneva Convention IV: Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict ................................... 137

Means and Methods of Warfare ............................................................................................ 163

War Crimes and Command Responsibility ........................................................................... 199

Appendix A . US Position regarding ICC ....................................................................... 227

Appendix B. Milosevic Indictment Excerpt ................................................................... 233

The Law of War and Military Operations Other Than War ................................................. 239

Appendix A. CPL and Civilian Detainment ................................................................ 260

Appendix B. CPL and the Treatment of Property .......................................................... 266

Appendix C . CPL and Displaced Persons ...................................................................... 269

Human Rights ....................................................................................................................... 279

Appendix A. Universal Declaration of Human Rights .................................................. 289

HISTORY OF' THE LAW OF WAR

REFERENCES

1.

Dept. of Army, Pamphlet 27-1, Treaties Governing Land Warfare (7 December 1956) [-hereinafter DAPAM 27- 11 (reprinted in Documentary Supplement).

2.

Dept. of Army, Pamphlet 27-1-1, Protocols To The Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949 (1 September 1979). [hereinafter DA PAM 27-1-11 (reprinted in Documentary Supplement).

3.

Dept. of Army, Pamphlet 27-161-2, Intemational Law, Vol. I1 (23 October 1962). bereinafter DA PAM 27-161-21 (no longer in print).

4.

International Committee of the Red Cross, Commentary on the Geneva Convention (I) for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armed Forces in the Field (Jean S. Pictet ed., 1952) bereinafter Pictet]

5.

Leon Friedman, The Law of War--A Documentary History--Vol. I (1972).

6.

Lothar Kotzsch, The Concept of War In Contemporary History and International Law (1956).

7.

Julius Stone, Legal Controls of International Conflict (1954).

8.

John N. Moore, National Security Law (1990).

9.

L. Oppenheim, Intemational Law Vol. I1 Disputes, War and Neutrality (7"' ed. 1952).

10.

Gerhard von Glahn, Law Among Nations (1992).

11.Michael Walzer, Just and Unjust Wars (1977).

12. Percy Bordwell, The Law of War Between Belligerents: A History and Commentary (1908).

13.

Chris Jochnick and Roger Normand, The Legitimization of Violence: A Critical History of the Laws of War, 35 HARV.INT'L.L. J. 49 (Winter, 1994).

14.

Eric S. Krauss and Mike 0.Lacey, Utilitarian vs. Humanitarian: The Battle Over the Law of War,PARAMETERS,

Summer 2002.

15. Scott Morris, The Laws of War: Rules for Warriors by Warriors, ARMY LAWYER,

Dec. 1997.

16. Gregory P. Noone, The History and Evolution of the Law of War Prior to World War II,47 NAVALL. REV. 176 (2000).

I. INTRODUCTION.

A. OBJECTIVES:

1.

Identify common historical themes that continue to support the validity of laws regulating warfare.

2.

Identify the two "prongs" of legal regulation of warfare.

3.

Trace the historical "cause and effect" evolution of laws related to the conduct of war.

1

Chup/ei-1 Hi.,tory i?j LO Irk'

4. Begin to analyze the legitimacy of injecting law into warfare.

B. The "law of war" is the "customary and treaty law applicable to the conduct of warfare on land and to relationships between belligerents and neutral states." (FM 27-10, para. 1). It "requires that belligerents refrain from employing any kind or degree of violence which is not actually necessary for military purposes and that they conduct hostilities with regard for the principles of humanity and chivalry." FM 27-10, para. 3. It is also referred to as the Law of Armed Conflict or Humanitarian Law, though some object to the latter reference as it is sometimes used to broaden the traditional content of the law of war.

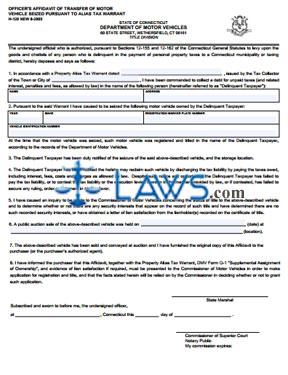

C. As illustrated by the diagram on page 3, the law of war is a part of the broader body of law known as public international law. International law is defined as "rules and principles of general application dealing with the conduct of states and of international organizations and with their relations inter se, as well as some of their relations with persons, natural or juridical." (Restatement of the Law, Third, Foreign Relations Law of the United States, 5 101.) Public international law is that portion of international law that deals mainly with intergovernmental relations.

D. The law of war has evolved to its present content over millennia based on the actions and beliefs of nations. It is deeply rooted in history and an understanding of this history is necessary to understand current law of war principles.

Chupter 1 History of LOW

International Law

r------

I

Private Law -Public Law -commercial law intergovernmental

Law of Armed Law of Peace Conflict

Conflict Rules of

Management Hostilities

(Jus ad Bellum) (Jusin Bello)

Hague Conventions (means & methods)

[ Geneva4 Conventions I (humanitarian)

E. WHAT IS WAR? "It is possible to argue almost endlessly about the legal definition of "war." (Pictet, p. 32). .

1. International Legal Definition: The Four Elements Test.

a.

A contention;

b.

Between at least two nation states;

c.

Wherein armed force is employed;

d.

With an intent to overwhelm.

2. War versus Armed Conflict. Historically, only conflict meeting the four elements test for "war" triggered law of war application. Accordingly, some nations asserted the law of war was not triggered by all instances of armed conflict. As a result, the applicability of the law of war depended upon the subjective national classification of a conflict.

a. Post WW I1 response. Recognition of a state of war is no longer required to trigger the law of war. Instead, the law of war is applicable to any

international armed conflict:

(1)"Any difference arising between two States and leading to the intervention of armed forces is an armed conflict . . . [i]t makes no difference how long the conflict lasts, or how much slaughter takes place." (Pictet, p. 32).

11. THE UNIFYING THEMES OF THE LAW OF WAR.

A. Law exists to either (1) prevent conduct or, (2) control conduct. These characteristics permeate the law of war, as exemplified by the two prongs. Jus ad Bellurn serves to prevent conduct, while Jus in Bello serves to regulate or control conduct.

1. Validity. Although critics of regulating warfare cite historic examples of violations of evolving laws of war, history provides the greatest evidence of the validity of this body of law.

a.

History shows that in the vast majority of instances the law of war works. Despite the fact that the rules are often violated or ignored, it is clear that mankind is better off with them than without them.

b.

History demonstrates that mankind has always sought to limit the affect of conflict on the combatants and has come to regard war not as a state of anarchy justifying infliction of unlimited suffering, but as an unfortunate reality which must be governed by some rule of law.

(1)This point is exemplified by Article 22 of the Hague Convention: "the right of belligerents to adopt means of injuring the enemy is not unlimited, and this rule does not lose its binding force in a case of necessity."

(2)That regulating the conduct of warfare is ironically essential to the preservation of a civilized world was exemplified by General MacArthur, when in confirming the death sentence for Japanese General Yamashita, he wrote: "The soldier, be he friend or foe, is charged with the protection of the weak and unarmed. It is the very essence and reason of his being. When he violates this sacred trust, he not only profanes his entire cult but threatens the fabric of international society."

B. The trend toward regulation grew over time in scope and recognition. When considering whether these rules have validity, the student and the teacher (judge advocates teaching soldiers) must consider the objectives of the law of War.

1.

The purpose of the law of war is to (1) integrate humanity into war and (2) serve as a tactical combat multiplier.

2.

The validity of the law of war is best explained in terms of both objectives. For instance, many site the German massacre at Malmedy as providing American forces with the inspiration to break the German advance during World War 11's Battle of the Bulge. Accordingly, observance of the law of war denies the enemy a rallying cry against difficult odds.

111. JUS AD BELLUM AND JUS IN BELL0

A. The law of armed conflict is generally divided into two major categories, Jus ad Bellum and Jus in Bello.

B. Jus ad Bellum is the law dealing with conflict management, of the laws regarding how states initiate armed conflict; under what circumstances was the use of military power legally and morally justified.

C. Jus in Bello is the law governing the actions of states once conflict has started; what legal and moral restraints apply to the conduct of waging war.

D. Both categories of the law of armed conflict have developed over time, drawing most of their guiding principles from history.

E. The concepts of Jus ad Bellum and Jus in Bello developed both unevenly and concurrently. For example, during the majority of the Jus ad Bellum period, most societies only dealt with rules concerning the legitimacy of using force. Once the conditions were present that justified war, there were often no limits on the methods used to wage war. At a certain point both theories began to evolve together.

IV. ORIGINS OF JUS AD BELLUM

A. Jus ad Bellum: Legitimate War. Law became an early player in the historical development of warfare. The earliest references to rules regarding war referred to the conditions that justified resort to war legally and morally.

1.

Greeks: began concept of Jus ad Bellum, wherein a city state was justified in resorting to the use of force if a number of conditions existed (if the conditions existed the conflict was blessed by the gods and was just). In the absence of these conditions armed conflict was forbidden.

2.

Romans: formalized laws and procedures that made the use of force an act of last resort. Rome dispatched envoys to the nations against whom they had grievances, and attempted to resolve differences diplomatically. The Romans also are credited with developing the requirement for declaring war. Cicero wrote that war must be declared to be just.

3.

The ancient Egyptians and Sumerians (2nd millennium B.C.) generated rules defining the circumstances under which war might be initiated.

4.

The ancient Hittites required a formal exchange of letters and demands before initiating war. In addition, no war could begin during planting season.

5.

Deuteronomy 20. "Before attacking an enemy city make an offer of peace."

Chapter 1 History of'LOW

V. THE HISTORICAL PERIODS.

A. THE JUST WAR PERIOD.

1.

This period ranged from 335 B.C. to about 1800 A.D. The primary tenant of the period was determination of a "just cause" as a condition precedent to the use of military force.

2.

Just Conduct Valued Over Regulation of Conduct. The law during this period focused upon the first prong of the law of war (Jus ad Bellum). If the reason for the use of force was considered to be just, whether the war was prosecuted fairly and with humanity was not a significant issue.

3.

Early Beginnings: Just War Closely Connected to Self-Defense.

a.

Aristotle (335 B.C.) wrote that war should only be employed to (1) prevent men becoming enslaved, (2) to establish leadership which is in the interests of the led, (3) or to enable men to become masters of men who naturally deserved to be enslaved.

b.

Cicero refined Aristotle's model by stating that "the only excuse for going to war is that we may live in peace unharmed ...."

4. The Era of Christian Influence: Divine Justification.

a.

Early church leaders forbade Christians from employing force even in self-defense. This position became less and less tenable with the expansion of the Christian world.

b.

Church scholars later reconciled the dictates of Christianity with the need to defend individuals and the state by adopting a Jus ad Bellum position under which recourse to war was just in certain circumstances (6th century A.D.).

5. Middle Ages. Saint Thomas Aquinas (12th century A.D.) (within his Summa Theologica) refined this "just war" theory when he established the three conditions under which a just war could be initiated:

a.

with the authority of the sovereign;

b.

with a just cause (to avenge a wrong or fight in self-defense); and

c.

so long as the fray is entered into with pure intentions (for the advancement of good over evil). The key element of such an intention was to achieve peace. This was the requisite "pure motive."

6. Juristic Model. Saint Thomas Aquinas' work signaled a transition of the Just War doctrine from a concept designed to explain why Christians could bear arms (apologetic) towards the beginning of a juristic model.

a.

The concept of "just war" was initially enunciated to solve the moral dilemma posed by the adversity between the Gospel and the reality of war. With the increase in the number of Christian nation-states, this concept fostered an increasing concern with regulating war for more practical reasons.

b.

The concept of just war was being passed from the hands of the theologians to the lawyers. Several great European jurists emerged to document customary laws related to warfare. Hugo Grotius (1583-1645) produced the most systematic and comprehensive work, On the Law of War and Peace. His work is regarded as the starting point for the development of the modern law of war.

c.

While many of the principles enunciated in this work were consistent with church doctrine, Grotius boldly asserted a non-religious basis for this law. According to Grotius, the law of war was not based on divine law, but on recognition of the true natural state of relations among nations. Thus, the law of war was based on natural, and not divine law.

7. The End of the Just War Period. By the time the next period emerged, the Just War Doctrine had generated a widely recognized set of principles that represented the early customary law of war. The most fundamental of these principles are:

a.

A decision to wage war can be reached only by legitimate authority (those who rule, e.g. the sovereign).

b.

A decision to resort to war must be based upon a need to right an actual wrong, in self-defense, or to recover wrongfully seized property.

c.

The intention must be the advancement of good or the avoidance of evil.

d.

In war, other than in self-defense, there must be a reasonable prospect of

victory.

8

C'hopter.1 History of LOW

e.

Every effort must be made to resolve differences by peaceful means, before resorting to force.

f.

The innocent shall be immune from attack.

g.

The amount of force used shall not be disproportionate to the legitimate objective.

B.

THE WAR AS FACT PERIOD (1800-1918).

1. Generally. This period saw the rise of the nation state as the principle element used in foreign relations. These nation states transformed war from a tool to achieve justice to something that was a legitimate tool to use in pursuing national policy objectives.

a.

Just War Notion Pushed Aside. Natural or moral law principles replaced by positivism that reflected the rights and privileges of the modem nation state. Law is based not on some philosophical speculation, b~rt on rules emerging from the practice of states and international conventions.

b.

Basic Tenets: Since each state is sovereign, and therefore entitled to wage war, there is no international legal mandate, based on morality or nature, to regulate resort to war (realpolitik replaces justice as reason to go to war). War is (based upon whatever reason) a legal and recognized right of statehood. In short, if use of military force would help a nation state achieve its policy objectives, then force may be used.

c.

Clausewitz. This period was dominated by the realpolitik of Clausewitz. He characterized war as a continuation of a national policy that is directed at some desired end. Thus, a state steps from diplomacy to war, not always based upon a need to correct an injustice, but as a logical and required progression to achieve some policy end.

d.

Things to Come. The War as Fact Period appeared as a dark era for the rule of law. Yet, a number of significant developments signaled the beginning of the next period.

2. Established the Foundation for upcoming "Treaty Period." Based on the

"positivist" view, the best way to reduce the uncertainty attendant with

conflict was to codify rules regulating this area.

a.

Intellectual focus began shift toward minimizing resort to war and/or mitigating the consequences of war.

b.

EXAMPLE: National leaders began to join the academics in the push to control the impact of war (Czar Nicholas and Theodore Roosevelt pushed for the two Hague Conferences that produced the Hague Conventions and Regulations).

C.

JUS CONTRA BELLUM PERIOD.

Clruptrr 1 Hisioty of LOW

1. Generally. World War I represented a significant challenge to the validity of the "war as fact" theory.

a.

In spite of the moral outrage directed towards the aggressors of that war, legal scholars unanimously rejected any assertion that initiation of the war constituted a breach of international law.

b.

World leaders struggled to give meaning to a war of unprecedented carnage and destruction. The "war to end all wars" sentiment manifested itself in a shift in intellectual direction leading to the conclusion that aggressive use of force must be outlawed.

2. Jus ad Bellum Changes Shape. Immediately before this period began, the Hague Conferences (1 899- 1907) produced the Hague Conventions, which represented the last multilateral law that recognized war as a legitimate device of national policy. While Hague law concentrates on war avoidance and limitation of suffering during war, this period saw a shift toward an absolute renunciation of aggressive war.

a.

League of Nations. First time in history that nations agreed upon an obligation under the law notto resort to war to resolve disputes or to secure national policy goals (Preamble). The League was set up as a component to the Treaty of Versailles, largely because President Wilson felt that the procedural mechanisms put in place by the Covenant of the League of Nations would force delay upon nations bent on war. During these periods of delay peaceful means of conflict management could be brought to bear.

b.

Eighth Assembly of League of Nations: banned aggressive war (questionable legal effect of resolution). However, the League did not attempt to enforce this duty (except as to Japan's invasion of Manchuria in 1931).

c.

Kellogg-Briand Pact (1928). Officially referred to as the Treaty for the Renunciation of War, it banned aggressive war. This is the point in time generally thought of as the "quantum leap." For the first time, aggressive war is clearly and categorically banned. In contradistinction from the post WW I period, this treaty established an international legal basis for the post WW I1 prosecution of those responsible for waging aggressive war.

d.

Current Status of Pact. This treaty remains in force today. Virtually all commentators agree that the provisions of the treaty banning aggressive war have ripened into customary international law.

Chapter I History of LOW

3. Use of force in self-defense remained unregulated. No law has ever purported to deny a sovereign the right to defend itself. Some commentators stated that the use of force in the defense is not war. Thus, war has been banned altogether.

D. POST WORLD WAR I1 PERIOD.

1.

Generally. The Procedural requirements of the Hague Conventions did not prevent World War I; just as the procedural requirements of the League of Nations and the Kellogg-Briand Pact did not prevent World War 11. World powers recognized the need for a world body with greater power to prevent war, and international law that provided more specific protections for the victims of war.

2.

Post-WWII War Crimes Trials (Nuremberg, Tokyo, and Manila Tribunals). The trials of those who violated international law during World War I1 demonstrated that another quantum leap had occurred since World War I.

a.

Reinforced tenants of Jus ad Bellum and Jus in Bello, and ushered in the era of "universality," establishing the principle that all nations are bound by the law of war based on the theory that law of war conventions largely reflect customary international law.

b.

World focused on ex post facto problem during prosecution of war crimes. The universal nature of law of war prohibitions, and the recognition that they were at the core of international legal values Gus cogens), resulted in the legitimate application of those laws to those tried for violations.

E.

The United Nations Charter. Continues shift to outright ban on war. Extended ban to not only war, but through Article 2(4), also "the threat or use of force."

1.

Early Charter Period. Immediately after the negotiation of the Charter in 1945, many nations and commentators assumed that the absolute language in the Charter's provisions permitted the use of force only if a nation had already suffered an armed attack.

2.

Contemporary Period. Most nations now agree that a nation's ability to defend itself is much more expansive than the provisions of the Charter seem to permit based upon a literal reading. This view is based on the conclusion that the inherent right of self-defense under customary international law was supplemented, and not displaced by the Charter. This remains a controversial issue.

F. Jus ad Bellum continues to evolve. Current doctrines such as anticipatory self- defense and preemption are adapted to meet today's circumstances.

VI. ORIIGINS OF JUS IN BELL0

A. Jus in Bello: Regulation of Conduct During War. The second body of law that began to develop dealt with rules that control conduct during the prosecution of a war to ensure that it is legal and moral.

1. Ancient China (4th century B.C.). Sun Tzu's The Art of War set out a number of rules that controlled what soldiers were permitted to do during war:

a.

captives must be treated well and cared for; and

b.

natives within captured cities must be spared and women and children respected.

2.

Ancient India (4th century B.C.). The Hindu civilization produced a body of rules codified in the Book of Manu that regulated in great detail land warfare.

3.

Ancient Babylon (7th century B.C.). The ancient Babylonians treated both captured soldiers and civilians with respect in accordance with well- established rules.

B. Jus in Bello received little attention until late in the Just War period. This led to the emergence of a Chivalric Code. The chivalric rules of fair play and good treatment only applied if the cause of war was "just" from the beginning.

12 Chapter I Histo1.y oj'LOW

1.

Victors were entitled to spoils of war, only if war was just.

2.

Forces prosecuting an unjust war were not entitled to demand Jus in Bello during the course of the conflict.

3.

Red Banner of Total War. Signaled a party's intent to wage absolute war (Joan of Arc announced to British "no quarter will be given").

C. During the War as Fact period, the focus began to change from Jus ad Bellum to Jus in Bello also. With war a recognized and legal reality in the relations between nations, the focus on mitigating the impact of war emerged.

1.

A Memory of Solferino (Henry Dunant's graphic depiction of the bloodiest battles of Franco-Prussian War). His work served'as the impetus for the creation of the International Committee of the Red Cross and the negotiation of the First Geneva Convention in 1864.

2.

Francis Lieber. Instructions To Armies in the Field (1863). First modem restatement of the law of war issued in the form of ~eneral Order 100 to the Union Army during the American Civil War.

3.

International Revulsion of General Sherman's "War is Hell" Total War. Sherman was very concerned with the morality of war. His observation that war is hell demonstrates the emergence and reintroduction of morality. However, as his March to the Sea demonstrated, Sherman only thought the right to resort to war should be regulated. Once war had begun, he felt it had no natural or legal limits. In other words he only recognized the first prong (Jus ad Bellum) of the law of war.

4.

At the end of this period, the major nations held the Hague Conferences (1 899-1907) that produced the Hague Conventions. While some Hague law focuses on war avoidance, the majority of the law dealt with limitation of suffering during war.

D. Geneva Conventions (1949).

1. Generally

a.

"War" v. "Armed Conflict." Article 2 common to all four Geneva Conventions ended this debate. Article 2 asserts that the law of war applies in any instance of international armed conflict.

b.

Four Conventions. A comprehensive effort to protect the victims of war.

c.

Birth of the Civilian's Convention. A post war recognition of the need to specifically address this class of individuals.

2.

The four conventions are considered customary international law. This means even if a particular nation has not ratified the treaties, that nation is still bound by the principles within each of the four treaties because they are merely a reflection of customary law that all nations states are already bound

by.

3.

Concerned with national and not international forces? In practice, forces operating under U.N. control comply with the Conventions.

4.

Clear shift towards a true humanitarian motivation: "the Conventions are coming to be regarded less and less as contracts on a basis of reciprocity concluded in the national interest of each of the parties, and more and more as solemn affirmations of principles respected for their own sake . . ."

5.

The 1977Protocols.

a.

Generally. These two treaties were negotiated to supplement the four Geneva Conventions.

b.

Protocol I. Effort to supplement rules governing international armed conflicts.

c.

Protocol 11. Effort to extend protections of conventions to internal conflicts.

VII. WHY REGULATE WARFARE?

A. Motivates the enemy to observe the same rules.

B. Motivates the enemy to surrender.

C. Guards against acts that violate basic tenets of civilization.

1.

Protects against unnecessary suffering.

2.

Safeguards certain fundamental human rights.

D. Provides advance notice of the accepted limits of warfare.

E. Reduces confusion and makes identification of violations more efficient.

14 Chupter I History of 120W

F. Helps restore peace.

VIII. CONCLUSION.

"Wars happen. It is not necessary that war will continue to be viewed as an

instrument of national policy, but it is likely to be the case for a very long time. Those

who believe in the progress and perfectibility of human nature may continue to hope

that at some future point reason will prevail and all international disputes will be

resolved by nonviolent means . .. Unless and until that occurs, our best thinkers

must continue to pursue the moral issues related to war. Those who romanticize

war do not do mankind a service; those who ignore it abdicate responsibility for the

future of mankind, a responsibility we all share even if we do not choose to do so."

Clrupter I Ifi.stoty of LOW

NOTES

Clmpler 1

History of LOW

NOTES

NOTES

Chapter 2

FRAMEWORK OF THE LAW OF WAR

REFERENCES

1.

Geneva Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armed Forces in the Field, August 12, 1949, T.I.A.S. 3362. (GWS)

2.

Geneva Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of Wounded, Sick, and Shipwrecked Members at Sea, August 12, 1949, T.I.A.S. 3363. (GWS Sea)

3.

Geneva Convention Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War, August 12, 1949, T.I.A.S. 3364. (GPW)

4.

Geneva Convention Relative to the Treatment of Civilian Persons in Time of War, August 12, 1949 T.I.A.S. 3365. (GC)

5.

The 1977 Protocols Additional to the Geneva Conventions, December 12, 1977, reprinted in 16

I.L.M. 1391, DEP'T OF Amy, PAMPHLET

27-1-1 (GP I & 11). (Reprinted in LOW Documentary Supplement).

6. Commentary on the Geneva Conventions, (Pictet ed. 1960).

7. DEP'TOF ARMY, PAMPHLET GOVERNING (7 Dec. 1956). 27-1, TREATIES LAND WARFARE,

8. DEP'TOF ARMY,PAMPHLET LAW, VOLUME 27-161-2, INTERNATIONAL I1 (23 Oct. 1962) (no longer in print).

9. DEP'TOF ARMY, FIELD MANUAL27-10, THE LAW OF LAND WARFARE (18 July 1956).

10.NAVALWARFARE 1-14MCWP 5-2.1/COMDTPUB 5800.7 THE COMMANDER'S

PUBLICATION HANDBOOKON THE LAWOF NAVALOPERATIONS ( Oct. 1995).[ (FORMERLY NWP 9/FMFM 1-10 (REVISION

A),

1 1. AIR FORCE PAMPHLET LAW OF ARMED CONFLICT

1 10-3 1, INTERNATIONAL -THE CONDUCT AND AIR OPERATIONS

(19 NOV. 1976).

12.

MORNS GREENSPAN, THE MODERN LAWOF LAND WARFARE (1959).

13.

DIETRICHSCHINDLER& JIRI TOMAN, THE LAW OF ARMEDCONFLICT(1988).

14.

HILAIRE INTERNATIONAL LAW (1990).

MCCOUBREY, HUMANITARIAN

15.

HOWARDS. LEVIE, OF INTERNATIONAL CONFLICT(1986).

THE CODE ARMED

I. OBJECTIVES.

A. Become familiar with the primary sources of the law of war.

B. Become familiar with the "language" of the law.

C. Understand how the law of war is "triggered."

19

Chuptrr 2 Fr~mzeworkof LOW

D. Become familiar with the role of the 1977 Protocols to the Geneva Conventions of 1949.

E. Be able to distinguish "humanitarian" law from human rights law.

11. THE LANGUAGE OF THE LAW. THE FIRST STEP IN UNDERSTANDING THE LAW OF WAR IS TO UNDERSTAND THE "LANGUAGE" OF THE LAW. THIS REFERS TO UNDERSTANDING SEVERAL KEY TERMS AND CONCEPTS THAT ARE WOVEN THROUGH THIS BODY OF LAW.

A. Sources of Law.

1. Cukitomary International Law. This can be best understood as the "unwritten" rules that bind all members of the community of nations.

a.

Customary law is defined as that law resulting from the general and consistent practice of states followed from a sense of legal obligation. Customary international law and treaty law are equal in stature, with the later in time controlling.

b.

It is possible for a nation not to be bound by a customary norm of international law if that nation persistently objected to the norm as it was developing and continues to declare that it is not bound by that customary international law.

c.

Many principles of the law of war fall into this category of international law. Customary international law can also provide background with which to understand later codification of laws of war into treaty. Restatement of the Law, Third, Foreign Relations Law of the United States, 5 102. Therefore while much of the law of war is now codified, customary international law of war is still relevant.

2. Conventional International Law. This term refers to codified rules binding on nations based on express consent. The term "treaty" best captures this concept, although other terms are used to refer to these: Convention, Protocol, and Attached Regulations.

a.

Norms of customary international law can either be codified by subsequent treaties, or emerge out of new rules created in treaties.

b.

Many law of war principles are both reflected in treaties, and considered customary international law. The significance is that once a principle attains the status of customary international law, it is binding on all nations, not just treaty signatories.

B.

While there are numerous law of war treaties in force today, most of them fall within two broad categories.

1. The Targeting Method. This prong of the law of war is focused on regulating the means and methods of warfare, i.e. tactics, weapons, and targeting decisions.

a.

This method is exemplified by the Hague law, consisting of the various Hague Conventions of 1899 as revised in 1907, plus the 1954 Hague Cultural Property Convention and the 1980 Conventional Weapons Convention.

b.

The rules relating to the methods and means of warfare are primarily derived from articles 22 through 41 of the Regulations Respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land [hereinafter HR] annexed to Hague Convention IV. HR, art. 22-4 1. Article 22 states that the means of injuring the enemy are notunlimited.

c.

Treaties. The following treaties, limiting specific aspects of warfare, are another source of targeting guidance. Several of these treaties are discussed more fully in the Means and Methods Outline section on weapons.

(1) Gas. Geneva Protocol of 1925 prohibits use in war of asphyxiating, poisonous, or other gases. The US reserved the right to respond with chemical weapons to a chemical attack by the other side. The more recent Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), however, prohibits production, stockpiling, and use of chemical weapons (even in retaliation). The U.S. ratified the CWC in April 1997.

(2)Cultural Property. The 1954 Hague Cultural Property Convention prohibits targeting cultural property, and sets forth conditions when cultural property may be attacked or used by a defender.

(3)Biological Weapons. The 1925 Geneva Protocol prohibits biological weapons. However, the 1972 Biological Weapons Convention prohibits their use in retaliation, as well as production, manufacture, and stockpiling.

(4)Conventional Weapons. The 1980 Conventional Weapons Treaty restricts or prohibits the use of certain weapons deemed to cause unnecessary suffering or to be indiscriminate: Protocol I -non-detectable fragments; Protocol I1 -mines, booby traps and other devices; Protocol 111 -incendiaries; and Protocol IV- laser weapons. The U.S. has ratified the treaty by ratifying Protocols I and 11. The Senate is currently reviewing Protocols I11 and IV for its advice and consent to ratification. The treaty is often referred to as the UNCCW -United Nations Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons. As of 1 January 2003,90 nations are now Party to the Treaty. Protocols I, 11, 111, and IV have entered into force.

2. The Protect and Respect Method. This prong of the law of war is focused on establishing non-derogable protections for the "victims of war."

a. This method is exemplified by the 4 Geneva Conventions of 1949. Each of these four "treaties" is devoted to protecting a specific category of war victims:

(1)GWS: Wounded and Sick in the Field.

(2)GWS Sea: Wounded, Sick, and shipwrecked at Sea.

(3)GPW: Prisoners of War.

(4)

GC: Civilians.

b.

The Geneva Conventions entered into force on 21 October 1950. The President transmitted the Conventions to the United States Senate on 26 April 195 1. The United States Senate gave its advice and consent to the Geneva Conventions on 2 August 1955.

3. The "Intersection." In 1977, two treaties were created to "supplement" the 1949 Geneva Conventions. These treaties are called the 1977 Protocols (GPI & GPII).

a. Motivated by International Committee of the Red Cross' belief that the four Geneva Conventions and the Hague Regulations insufficiently covered certain areas of warfare in the conflicts following WWII, specifically aerial bombardments, protection of civilians, and wars of

22

Chupter 2 Acmewovk ofLOCT.'

national liberation. While the purpose of these "treaties" was to supplement the Geneva Conventions, they in fact represent a mix of both the Respect and Protect method, and the Targeting method.

b. Status.

(1) As of December 2003, 161 nations have become Parties to GPI and 156 nations have become Parties to GPII.

(2)Unlike The Hague and Geneva Conventions, the U.S. has never ratified either of these Protocols. Portions, however, do reflect state practice and legal obligations --the key ingredients to customary international law.

c. U.S. Position:

(1)New or expanded areas of definition and protection contained in Protocols include provisions for: medical aircraft, wounded and sick, prisoners of war, protections of the natural environment, works and installations containing dangerous forces, journalists, protections of civilians from indiscriminate attack, and legal review of weapons.

(2)

US views the following Protocol I articles as either customaw international law or acceptable practice though not legally binding:

(a)

5 (appointment of protecting powers);

(b)

10 (equal protection of wounded, sick, and shipwrecked);

(c)

11(guidelines for medical procedures);

(d)

12-34 (medical units, aircraft, ships, missing and dead persons);

(e)

35(1)(2) (limiting methods and means of warfare);

(037 (perfidy prohibitions);

(g)

38 (prohibition against improper use of protected emblems);

(h)45 (prisoner of war presumption for those who participate in the hostilities);

(i)

51 (protection of the civilian population, except para. 6 --reprisals);

Cj) 52 (general protection of civilian objects);

(k)

54 (protection of objects indispensable to the survival of the civilian population);

(1)

57-60 (precautions in attack, undefended localities, and demilitarized zones);

(m)

62 (civil defense protection);

(n)

63 (civil defense in occupied territories);

(0)

70 (relief actions);

(p)

73-89 (treatment of persons in the power of a party to the conflict; women and children; and duties regarding implementation of GPI).

(3)The US specifically objects to the following articles:

(a)

l(4) (applicability to certain types of armed conflicts);

(b)

35(3) (environmental limitations on means and methods of warfare);

(c)

39(2) (use of enemy flags and insignia while engaging in attacks); (d)44 (combatants and prisoners of war (portions));

(e)

47 (non-protection of mercenaries);

(f)

5 5 (protection of the natural environment); and

(g)

56 (protection of works and installations containing dangerous iorces).

See Michael J. Matheson, The United States Position on the

Relation of Customary International Law to the 1977 Protocols

Additional to the 1949 Geneva Conventions, 2 Am. U. J. Int'l & Pol'y

419, 420 (1987).

4. Regulations. Implementing targeting guidance for US Armed Forces is found in both Joint and Service publications. Joint Pub 3-60, FM 27- 10 (Army), NWP 1-14MRMFM 1-10 (Navy and Marine Corps).

Chapter -7 Franwvor-k oj L0I.b'

C. Key Terms.

1.

Part, Section, Article . . . Treaties, like any other "legislation," are broken into sub-parts. In most cases, the Article represents the specific substantive provision.

2.

"Common Article." This is a critical term used in the law of war. It refers to a finite number of articles that are identical in all four of the 1949 Geneva Conventions. Normally these related to the scope of application and parties obligations under the treaties. Some of the Common Articles are identically numbered, while others are worded virtually the same, but numbered differently in various conventions. For example, the article dealing with special agreements is article 6 of the first three conventions, but article 7 of the Fourth Convention.

3.

Treaty Commentaries. These are works by official recorders to the drafting conventions for these major law of war treaties (Jean Pictet for the 1949 Geneva Conventions). These "Commentaries" provide critical explanations to many treaty provisions, and are therefore similar to "legislative history" in the domestic context.

D. Army Publications. There are three primary Army sources that reflect the rules that flow from "the big three:"

1.

FM 27-10: The Law of Land Warfare. This is the "MCM for the law of war. It is organized functionally based on issues, and incorporates rules from multiple sources.

2.

DA Pam 27-1. This is a verbatim reprint of The Hague and Geneva Conventions.

3.

DA Pam 27- 1-1. This is a verbatim reprint of the 1977 Protocols to the Geneva Conventions.

4.

Because these publications are no longer available, they have been compiled, along with many other key source documents, in the Law of War Documentary Supplement.

111. HOW THE LAW OF WAR IS TRIGERRED.

A. The Barrier of Sovereignty. Whenever international law operates to regulate the conduct of a state, it must "pierce" the shield of sovereignty.

1.

Normally, the concept of sovereignty protects a state from "outside interference with internal affairs." This is exemplified by the predominant role of domestic law in internal affairs.

2.

However, in some circumstances, international law "pierces the shield of sovereignty, and displaces domestic law from its exclusive control over issues. The law of war is therefore applicable only after the requirements for piercing the shield of sovereignty have been satisfied.

3.

The law of war is a body of international law intended to dictate the conduct of state actors (combatants) during periods of conflict.

a.

Once triggered, it therefore intrudes upon the sovereignty of the regulated state.

b.

The extent of this "intrusion" will be contingent upon the nature of the conflict.

B.

The Triggering Mechanism. The law of war includes a standard for when it becomes applicable. This standard is reflected in the Four Geneva Conventions.

1. Common Article 2 --International Armed Conflict: "[Tlhe present Convention shall apply to all cases of declared war or of any other armed conflict which may arise between two or more of the High Contracting Parties, even if the state of war is not recognized by one of them. "

a.

This is a true defacto standard. The subjective intent of the belligerents is irrelevant. According to the Commentary, the law of war applies to: "any difference arising between two States and leading to the intervention of armed forces."

b.

Article 2 effectively requires that the law be applied broadly and automatically from the inception of the conflict. The following two facts result in application of the entire body of the law of war:

(l)A dispute between states, and

(2)Armed conflict (see FM 27- 10, paras. 8 & 9).

(a) De facto hostilities are what are required. The drafters deliberately avoided the legalistic term war in favor of the broader principle of armed conflict. According to Pictet, this article was intended to be broadly defined in order to expand the reach of the Conventions to as many conflicts as possible.

c. Exception to the "state" requirement: Conflict between a state and a rebel movement recognized as belligerency.

(1) Concept arose as the result of the need to apply the Laws of War to situations in which rebel forces had the de facto ability to wage war.

(2)Traditional Requirements:

(a)

Widespread hostilities -civil war

+)Rebels have control of territory and pop!lati.on

(c)

Rebels have de facto government.

(d)Rebel military operations are conducted under responsible authority and observe the Law of War.

(e) Recognition by the parent state or another nation.

(3)

Recognition of a belligerent triggers the application of the Law of War, including The Hague and Geneva Conventions. The practice of belligerent recognition is in decline in this century. Since 1945, full diplomatic recognition is generally extended either at the beginning of the struggle or after it is successful (EX: The 1997 recognition of Mr. Kabila in Zaire).

d.

Controversial expansion of Article 2 --GPI.

(1)Expands Geneva Conventions application to conflicts previously considered internal ones: "[Alrmed conflicts in which peoples are fighting against colonial domination and alien occupation and against racist regimes in the exercise of their right of self determination." Art 1(4), GPI.

(2)U.S. has not yet ratified this convention because of objections to article l(4) and other articles. The draft of Protocol I submitted by the International Committee of the Red Cross to the 1974 Diplomatic Conference did not include the expansive application provisions.

e. Termination of Application (Article 5, GWS and GPW; Article 6, GC). (1)Final repatriation (GWS, GPW).

(2) General close of military operations (GC).

(3)Occupation (GC) --The GC applies for one year after the general close of military operations. In situations where the Occupying Power still exercises governmental functions, however, that Power is bound to apply for the duration of the occupation certain key provisions of the GC.

2. The Conflict Classification Prong of Common Article 3 --Conflicts which are not of an international character -internal armed conflict: "Armed conflict not of an international character occurring in the territory of one of the High Contracting Parties ...."

a.

These types of conflicts make up the vast bulk of the ongoing conflicts.

b.

Providing for the interjection of international regulation into a purely internal conflict was considered a monumental achievement for international law in 1949. But, the internal nature of these conflicts explains the limited scope of international regulation.

(1)Domestic law still applies -guerrillas do not receive immunity for their war-like acts, as would such actions if committed during an international armed conflict.

(2)Lack of effect on legal status of the parties. This is an essential clause without which there would be no provisions applicable to internal armed conflicts within the Cwwentions. Despite the r!ew Imguage, states have been reluctant to apply Article 3 protections explicitly for fear of conferring a degree of international legitimacy on rebels.

c. What is an "Internal Armed Conflict?" Although no objective set of criteria exist for determining the existence of a non-international armed conflict, Pictet lists several suggested criteria:

(1)Some conflict is more like isolated acts of violence, riots or banditry.

(2)Pictet establishes non-binding criteria for determining whether any particular situation rises to the level of armed conflict:

(a)

The group must have an organization,

(b)The members must be subject to some authority exercised within the organization,

(c)

The group must control some territory,

(d)The group must demonstrate respect for the laws of war though this is more often accepted as the group must not demonstrate an unwillingness to abide by the laws of war, and

(e)

The government must be forced to respond to the group with its own armed forces.

d.

Protocol IS, which was intended to supplement the substantive provisions of Common Article 3, formalized the criteria for the application of that convention to a non-international armed conflict.

(1)Under responsible command.

(2)Exercising control over a part of a nation so as to enable them to carry out sustained and concerted military operations and to implement the requirements of Protocol 11.

C. How do the Protocols fit in?

1. As indicated, the 1977Protocols to the Geneva Conventions of 1949 are supplementary treaties. Protocol I is intended to supplement the law of war related to international armed conflict, while Protocol I1 is intended to supplement the law of war related to internal armed conflict. Therefore:

a.

When you think of the law related to international armed conflict, also think of Protocol I;

b.

When you think of the law related to internal armed conflict, also think of Protocol IS.

2. Although the U.S. has never ratified either of these Protocols, their relevance continues to grow based on several factors:

a. The U.S. has stated it considers many provisions of Protocol I, and almost all of Protocol IS (all except for the limited scope of application in article l), to be customary international law. See Michael J. Matheson, Session One: The United States Position on the Relation of Customary

29

Chtrpter 2 Ftunmwrk of LO I,Y

International Law to the 1977Protocols Additional to the 1949 Geneva Conventions, 2 AM.U. J. INT'LL. POL'Y419,429-431 (1987).

b.

The argument that the entire body of Protocol I has attained the status of customary international law continues to gain strength.

c.

These treaties bind virtually all of our coalition partners.

d.

U.S. policy is to comply with Protocol I and Protocol I1 whenever feasible.

D.

U.S. Policy is to apply the principles and spirit of the Law of War during all operations, whether international armed conflict, internal armed conflict or situations short of armed conflict.

I.

DoD Directive 5 100.77 requires all members of the armed forces to "comply with the law of war during all armed conflicts, however such conflicts are characterized, and with the principles and spirit of the law of war during all operations."

2. CJCSI 5810.01B also states that "The Armed Forces of the U.S. . . . will comply with the law of war during all armed conflicts, however . . . characterized, and unless otherwise directed by competent authorities, principles and spirit . .. during OOTW."

E. What is the Relationship of the LOW with Human Rights?

1.

Human Rights Law refers to a totally distinct body of international law, intended to protect individuals from the arbitrary or cruel treatment of their government at all times.

2.

While the substance of human rights protections may be synonymous with certain law of war protections, it is critical to remember these are two distinct bodies of international law. The law of war is triggered by conflict. No such trigger is required for human rights law.

a. These two bodies of international law are easily confused, especially because of the use of the term "humanitarian law" to describe certain portions of the law of war.

NOTES

NOTES

NOTES

NOTES

THE UNITED NATIONS AND LEGAL BASES FOR THE

USE OF FORCE

REFERENCES

1.

U.N. Charter

2.

Treaty Providing for the Renunciation of War as an Instrument of National Policy (Kellogg- Briand Pact), done at Paris, August 27, 1928, 46 Stat. 2343, T.S. No. 796,2 Bevans 732, L.N.T.S. 57

3.

Agreement for the Prosecution and Punishment of the Major War Criminals of the European Axis Powers and Charter af the Intenlatianal Military Tribuiisl (Nilrzmbug Charier), dune a1 London, August 8, 1945,59 Stat. 1544, 82 U.N.T.S. 279

4.

U.N. General Assembly Resolution 337(V), Uniting for Peace, 5 U.H.

Related Topics

- Conduct in combat 1984

- US fighting code 1955

- Legal support operations

- Results of the attack on Pearl Harbor

- Procedure Dec-1947

- Procedure June-1944

- DA-PAM-27-17 05-1980

- An Overview of the United States Military

- Department of the navy manual opnav p22 -1115

- Naval Militia